Home » Teaching and Learning with Technology

Category Archives: Teaching and Learning with Technology

Macaulay Springboards: The Capstone as an Open Learning Eportfolio

a later version of this essay appears in Eportfolio as Curriculum, edited by Kathleen Blake Yancey, from Stylus Publishing.

Macaulay Springboards: The Capstone as an Open Learning Eportfolio

Joseph Ugoretz

Macaulay Honors College, CUNY

Introduction

A department office at a large public university is often a busy place. When I was an undergraduate, long ago, that was certainly the case. There was a small room, though, through a frosted-glass door, attached to the department office at the university where I was a student, and that room was not busy at all. Nobody, it seemed, ever went in or out that frosted door. One day, while waiting for a signature on a form, I opened the door and looked in. The room was full of filing cabinets, tall, grey and solidly packed against the walls. Even peeking through the door, I could see dust on the tops of the cabinets. These were not cabinets for frequently-used files.

Closing the door, I asked the department secretary what those were. “The honors thesis files,” she said. “To graduate with honors, you have to write a thesis. When you turn it in, I file it in there.”

I was certainly not an honors student myself. I wasn’t going to write a thesis, turn it in, or have it filed anywhere. But I was struck by the dusty, secluded fate of those theses.

Later, as a graduate student, I would write a thesis. And a dissertation. I would serve as an advisor and committee member receiving and evaluating many of them. Later still, I would see the movement (in many institutions) from the strict definition of a thesis to the somewhat broader concept of a capstone.

It’s with that concept that I want to begin.

The Capstone Requirement

A capstone project is a project of significant reach and scope designed to bring together and demonstrate a student’s learning in a specific major or program. According to the Association of American Colleges and Universities Brief Overview of High-Impact Educational Practices, “these culminating experiences require students nearing the end of their college years to create a project of some sort that integrates and applies what they’ve learned.” (https://www.aacu.org/leap/hips)

Generally speaking, a capstone, like a thesis, is supposed to culminate an educational experience and demonstrate that a student is now experienced and capable as a scholar and practitioner of the field in which she has been trained. The idea of the capstone is the idea of demonstrating and documenting and making clear that there is now a level of expertise and that there is a significant example of accomplishment that can be certified. Certification and exhibition are the keys to the capstone. Generally, these productions are judged, rated, accepted by some body of experts that rules them acceptable. A capstone is often supported by a course or group of courses, and may also include creative or artistic productions, but, more frequently than not, it is a long (usually, but not always, longer than the final assignment for a single course) formal paper. Often it takes the form of a “mini-dissertation,” complete with the sections that are often found in a dissertation or monograph produced by advanced scholars in the student’s chosen field.

My institution, Macaulay Honors College, is the honors college of the City University of New York. We have high-performing students across eight campuses, in over 300 different majors, united by a common identity as honors students, a common set of interdisciplinary seminars in critical thinking in the first two years, and a common set of rigorous academic requirements (spelled out in the student handbook at https://macaulay.cuny.edu/community/handbook/). One of those requirements, from the launch of the Honors College in 2001, has been the requirement to complete an honors thesis or capstone project. This is a common requirement in honors programs nationally; the National Collegiate Honors Council includes an honors thesis or capstone requirement as one of the “Basic Characteristics of a Fully Developed Honors College” (https://www.nchchonors.org/uploaded/NCHC_FILES/PDFs/NCHC_Basic_Characteristics-College_2017.pdf). At Macaulay, these projects were completed in the student’s own major or program on their own campus in most cases, and with the advisement of a faculty member from that department. The departments were responsible for assigning, reviewing and judging these projects.

Each year, advisors, campus directors, or the students themselves could nominate a thesis to be considered for the annual Thesis Award to be presented at commencement. These awards, in fact, were the only central review of the projects that took place, even though creating the projects was a central requirement. Almost every project nominated was, as should be expected from honors students, of high quality and broad scope, within a specific academic area. It was often difficult for the committee to select a winner, and the Thesis Award (later renamed the Capstone Award as that broader terminology became more current, but most awards were still given to students whose “capstone” was a thesis) was a pleasant surprise and a positive reinforcement for the students who received it.

Beginning in 2005, Macaulay Honors College also provided a course, a year-long (two-semester sequence) “thesis colloquium” as a purely optional or voluntary support mechanism for students who wanted extra structure and encouragement in completing their projects. This course accepted students from different majors or programs, as well as those who had interdisciplinary or hard-to-classify interests. It was a successful course and students who took the course had uniformly strong thesis projects at the end, as well as presentations at national and local undergraduate research conferences. Because it was optional and the students taking the course were self-selected, the numbers were always small—often only five or six students (out of a graduating class of approximately 500 in the honors college as a whole).

So this was the model at Macaulay—a not uncommon model for an honors college, or for many kinds of similar programs. Students were “required” (although the stringency of that requirement was somewhat inconsistent) to complete a project that was called (variously) a thesis or a capstone. The college (and the departments) provided varying levels of support and scaffolding for these projects, but for the most part, like a master’s thesis or a dissertation, they were independent projects, closely echoing the master’s thesis or dissertation but on a slightly smaller scale.

At the same time, we had introduced (beginning in 2008) our own eportfolio platform for all students. Eportfolios@Macaulay (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios), built in WordPress to allow maximum flexibility and individual control for students, was being used as a learning management system, as well as for group projects, individual student projects, student and faculty publications, class assignments, reflective travel journals, and a wide range of other purposes. The diversity and individuality of the eportfolios was appealing to students and the openness and flexibility of design and audience interaction was providing students with a strong motivation to do impressive work and spend time and energy on representing and reflecting on their learning.

As the then-Associate Dean for Teaching, Learning and Technology, I consulted with the instructor of the thesis colloquium course and showed her a few examples of the kinds of work students were doing with eportfolios. She was impressed by the students’ increased sense of ownership of their work, the integration of the diverse elements of their learning and the students’ participation in actively deciding what was most powerful and significant for inclusion in their eportfolios. She agreed to make a small preliminary adjustment to the thesis colloquium course. As an addition to the assignments and activities of the course, all of which led to the traditional thesis paper, we asked each of the students to create an eportfolio as a representation of the thesis project.

There was still a lengthy, well-researched written paper as a final outcome or production of the class, but some students (this started out as a non-required option) also elected to use an eportfolio to do something more than simply posting the paper online. They included early drafts, initial research directions that weren’t ultimately followed, and personal reflections. The first students to take this direction, in the spring of 2011, were those with interests that were more interdisciplinary, more connected to contemporary culture, and (not surprisingly) students who were more fluent and capable with digital tools.

And in the first projects that took this direction, we started to see a kind of richness, a kind of connection to the material, and a kind of life beyond the requirement, beyond the bachelor’s degree, and beyond the dusty secluded fate of the thesis room’s filing cabinets.

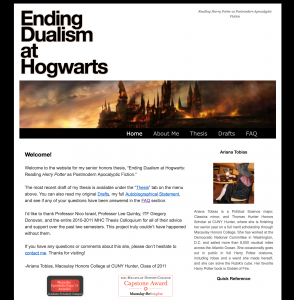

An early and successful example is “Ending Dualism at Hogwarts” (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/hpapocalypse/ ). There are several implications of this project that we noticed as the student was developing it and that we wanted to explore further. First, the student was able, through the “about me” section, as well as the FAQ, to provide a context and a connection to her own interests—to what made the thesis project interesting and valuable to her, beyond the scope of a requirement or assignment. “Why Harry Potter? Wouldn’t a more serious thesis be a better way to spend your time and energy?” the student asks in her FAQ list. Her answer,

An early and successful example is “Ending Dualism at Hogwarts” (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/hpapocalypse/ ). There are several implications of this project that we noticed as the student was developing it and that we wanted to explore further. First, the student was able, through the “about me” section, as well as the FAQ, to provide a context and a connection to her own interests—to what made the thesis project interesting and valuable to her, beyond the scope of a requirement or assignment. “Why Harry Potter? Wouldn’t a more serious thesis be a better way to spend your time and energy?” the student asks in her FAQ list. Her answer,

[the enormous popularity of these books] puts a lot of kids (and adults!) on the receiving end of a pretty explicit moral message about the importance of love, selflessness, tolerance and social justice. I don’t think it would be a waste of time to study how Rowling was able to achieve that kind of success. It would certainly be of interest to future authors and anyone else who also wants to promote those values in a way people can understand and enjoy. As someone who falls into that latter group, I think this project is just about as serious as it gets.

links her own project to a wider universe of discourse, as well as to her own identity and personality.

Also, in making design decisions, in thinking about how to present and organize her eportfolio site, she was able to think about categories and taxonomies for her work (when is a draft a draft? What makes a revision into a separate direction?). And because the site lives on the open web, she could make decisions about licensing (she chose a Creative Commons attribution-noncommercial license) and sharing. Not only could she decide that her work (or portions of her work that she selected) could move beyond the secluded file cabinet, but she could actually invite and encourage further interaction beyond the moment of “completion” of the project and the degree. (And in fact, this student does still link to the site on her LinkedIn profile as of this writing, more than six years after she graduated, now that she is fully established in a post-graduate career).

As an English teacher and student of literature, I like to think through terms and terminology, and dig into metaphors. Looking at “Ending Dualism at Hogwarts” and other projects from our early efforts to use eportfolios as part of a capstone experience, I started to think further about the term “capstone.” A capstone is a crowning accomplishment, a moment of completion.

It’s also, as an object, outside of any metaphorical meaning, in the most literal sense, a stone. This idea was somewhat troubling.

We didn’t (and don’t) want the final project of a student’s undergraduate degree to be something heavy and limiting. A “stone” that is a “cap” implies an end to further exploration, a finished structure that can’t be altered, a maximum high point that can’t be surpassed. A capstone is something that will sit in one place, immovable and unexamined. But that was not the kind of product that we wanted these projects to lead to, and it was not the kind of experience that we wanted for our students as they finished their undergraduate degrees.

The Springboard Concept

It was this thinking that led to the idea of the “springboard” course and the “springboard” project. In using the term “springboard,” I was thinking of the typical understanding of the term–a diving board at a swimming pool–but I was also drawing on some of my own long-past circus experience and imagining an act that we called the springboard, but that I’ve since learned is usually called the Russian Bar (http://www.fedec.eu/en/articles/416-russian-bar)  . The Russian Bar is held on the shoulders of two strong performers while a lighter agile performer (the “flyer”) does jumps, twirls and stunts using the launching impetus gained from the flexibility of the bar and the strength of the holders. I liked the idea of the project as a launching pad, an impulse to further growth and research and exploration, but more than that as a type of performance that was practiced but also public, meant to be shared and received by an audience, and actually even produced as a community effort. The student creating a springboard project, like the flyer on the Russian Bar, launches higher because she’s working from a flexible base and because there are others helping and pushing and working in concert. The individual performance is not completely or solely an individual effort based on individual strength. The concept emphasizes the reality (one of our desired outcomes) that every individual project is also collective. Without the participation of others, every project is incomplete and doesn’t go as far as it needs to.

. The Russian Bar is held on the shoulders of two strong performers while a lighter agile performer (the “flyer”) does jumps, twirls and stunts using the launching impetus gained from the flexibility of the bar and the strength of the holders. I liked the idea of the project as a launching pad, an impulse to further growth and research and exploration, but more than that as a type of performance that was practiced but also public, meant to be shared and received by an audience, and actually even produced as a community effort. The student creating a springboard project, like the flyer on the Russian Bar, launches higher because she’s working from a flexible base and because there are others helping and pushing and working in concert. The individual performance is not completely or solely an individual effort based on individual strength. The concept emphasizes the reality (one of our desired outcomes) that every individual project is also collective. Without the participation of others, every project is incomplete and doesn’t go as far as it needs to.

So with this metaphor in mind, with this new approach developed, we recruited students for a new version of what used to be our “thesis colloquium.” This course used the eportfolio as a central organizing element of the curriculum so that students from diverse academic interests and with diverse types of projects could work together to produce the products, the springboard projects, that would be represented in the eportfolio projects that would be (along with the written thesis project that they still produced) the final outcome of the course. Students in the course would develop eportfolios as part of the process of taking the course, and a final eportfolio (sometimes, but not always, the same site) would be the final presentation and product, in addition to whatever written thesis or creative work their academic program required. This was an additional requirement in a course that already had a heavy workload, but by integrating the springboard project (the eportfolio) into the thesis colloquium, the additional requirement could work as a support system for the existing requirements. Working on the springboard helped the work on the thesis, and the thesis helped the work on the springboard.

We launched the course with a website (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/springboard/) , developing the idea and proposing it to interested students, in the spring of 2013, for students who would be able to begin the course in the fall of 2013 to graduate with completed projects in the spring of 2014.  On the site, and in presentations for students to explain the idea, we started with a set of foundational principles:

On the site, and in presentations for students to explain the idea, we started with a set of foundational principles:

The springboard project:

-

Builds on a student’s earlier work and displays and reflects that work.

-

Proposes new directions, asks unanswered questions, poses unresolved dilemmas. In response to these challenges, the Springboard Project proposes specific research and learning pathways, providing a plan with clear goals and defined next steps

-

Includes personal reflection, uniting the affective and the cognitive elements of research.

-

Includes multimedia facets, utilizing appropriate tools and presentation techniques to present extra-textual resources.

-

Is presented to, and open to the interaction of, a wide public audience. It is a multidirectional communication.

These have remained as the guiding principles or ground rules for the course as it has continued to be offered, although we have continued to modify and develop the practical expressions of these principles. Each of these principles feeds directly into eportfolio-connected activities within the course curriculum, and each draws from the particular affordances of eportfolio pedagogy.

The Springboard Course

The springboard course, as the first principle states, is designed to be integrative, to pull together the disparate pieces of a student’s educational career (during college and before. And after). One way to help students make these connections, we have found, is to ask them to develop and post online digital, multimedia, educational timelines and to post those to their eportfolios. These digital timelines allow students to map out the course of their education from their earliest days (in elementary school and before) to the present and projecting into the future. Because the timelines are digital, students are able to include illustrative images, videos, links to websites and

other media to represent each of the separate moments or dates on the timeline—moments or dates that the students designated as significant in their educations—and to provide a sense of movement and progress that a static text-based timeline can’t easily communicate (we generally have students use the open-source TimelineJS tool for this). In most cases these separate dates or moments on the timelines were also developed and described in posts on the eportfolios. By building this assignment into the course curriculum and making the presentation of this wide-ranging timeline part of the presentation of the final project, we ask students to locate the final projects not only as culminations or final achievements of their education, but as connected pieces of the larger set of experiences. Students include classes and in-school activities and assignments in their timelines, but also life events and discoveries that are not connected directly to school (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/thevictoriaproject/timeline/ is one example. The student includes her daycare experience, various elementary and middle school teachers and projects that were memorable for her, college courses and study abroad trips, and more.

We also specifically ask students, in connecting their classwork and outside of classwork to these final projects, to look ahead, as well as behind. The eportfolios, by providing students a space to capture their research process and to reflect on it as it was ongoing, prompt a projection of their work into the future, beyond the confines of the undergraduate degree. Locating learning as a process that is ongoing and integrated helps students to see that they could plan out specific paths and directions (even when those were unclear at first…or even when they remained unclear) for uniting their interests and launching their learning into new areas and new interactions (“With my springboard project,” writes one student, “I sought to figure out what factors cause frustration in the math classroom, and then I looked at different techniques currently used by educators to reach ELL [English Language Learner] students. Hopefully, I can take these lessons with me, as I move forward with my goal of becoming a math teacher in the New York City public school classroom.” https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/mehnaj/springboard-project-improving-secondary-mathematics-instruction-for-english-language-learners/ ).

Similarly, we ask all the springboard students, no matter their field, to complete an assignment to create and post on the eportfolio a syllabus for a future class, that the student would teach, on the subject of her project. Even students who don’t have majors or career goals in education have years of experience with classes and syllabi (from the student side) and very strong opinions about what makes an effective or ineffective syllabus. This assignment gives students the opportunity to conceive of their education as something that gives them the role of expert, of sharer of expertise. Making their syllabi public on the eportfolio gives them a concrete reality and commitment to communicating their expertise and participating in the further development of their field.

One of the things that so often gets lost in the thesis or capstone project is, as our third principle tries to address, the affective component that is so critical to personal connection with the work. Advanced scholars know that the joy of research is what balances the frustration. The suspense and inspiration balance the tedium and the concentration. The eportfolio model, with reflection central and with a space (able to be prominently featured) for journaling the process as well as the product, allowed our springboard students to include, rather than denying, the different emotional responses they were having to the work. The students keep research journals right in their eportfolios, and that section can enliven the final product while still allowing the students to have and honor the emotional component as well as connecting it to the intellectual component (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/monsters/2016/11/08/salem-reflections/) “At some point in my research, I knew I would have to visit Salem,” begins one such journal from a student researching monsters in popular culture. Her journal entry details not just her research, but the entire process of dealing with an unfamiliar small town, problems with weather, businesses being closed and uncertain public transportation, and all the emotional effects of these obstacles.

When I could contact the family who tried to help me get out of Salem, I expressed my fears, uncertainties, gratitude, fatigue, and chill. I sent photos of how red my hands had become, jammed in the pockets of the winter jacket, and the inability to Facetime just covered the embarrassing tear-streaks over reddened cheeks as I tried to make my voice normal for them. I spoke more of the cold and the quick turn of the weather than the real life horror scenario I’d just run through.

And she connects her own experience to the subjects and her research,

My experience of uncertainty and fear was brief and largely psychologically built, but life in the colonies was filled with uncertainties and fears of that nature in day-to-day life. These could include insecurities about health of the self or young children, where mortality from sicknesses was much higher than today; insecurities about crops or catches leading to food insecurity or commercial insecurity; insecurities about the weather impacting home and property; insecurities about wild animals and other dangers of the wilderness surrounding them; and even insecurities in soulcraft, where Satan was real, his effects visible, devils prominent, and salvation uncertain and subject to rescindment.

In addition, because the eportfolio captures all the different steps of the process, students are able to evaluate for themselves what kinds of techniques (outlining, annotating, mind-mapping, interviewing, fieldwork, lab experimentation, etc.) are most effective for their own particular learning styles and topics. All these techniques and the students’ self-evaluations of them become pieces of the larger picture that the project presents—it’s not just about the product, but the entire process.

Eportfolios, unlike traditional written papers, provide the unique opportunity for the inclusion of multimedia materials. Interactive digital timelines are one such element, as discussed above. Beyond timelines, students include video, maps, drawings and photography, and audio files, as appropriate and connected to their projects.  This has proven especially helpful for students who are using the springboard option to pursue a more interdisciplinary approach than their major field of study would normally include. When a student’s academic interests include both biology and art, for example, and she wants her research and project to include the connections she sees in these two areas, an eportfolio is often the best space to make those connections. Because an eportfolio can take a range of different designs and make connections via hyperlink, allowing the connections to be multiple, multi-directional and digressive when necessary, a student can create a design that is actually about (for example) medical illustration as a unified, complete and integrated interest, rather than segregating her skills in only lab research or only charcoal drawing. She doesn’t need to ignore or short-change any of her interests or diminish the connections between and among them. (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/wormsandlearning/)

This has proven especially helpful for students who are using the springboard option to pursue a more interdisciplinary approach than their major field of study would normally include. When a student’s academic interests include both biology and art, for example, and she wants her research and project to include the connections she sees in these two areas, an eportfolio is often the best space to make those connections. Because an eportfolio can take a range of different designs and make connections via hyperlink, allowing the connections to be multiple, multi-directional and digressive when necessary, a student can create a design that is actually about (for example) medical illustration as a unified, complete and integrated interest, rather than segregating her skills in only lab research or only charcoal drawing. She doesn’t need to ignore or short-change any of her interests or diminish the connections between and among them. (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/wormsandlearning/)

The fifth principle of the springboard course and project is one that is uniquely fulfilled by the eportfolio, and one that is a direct response to the problem of the dusty filing cabinets in the thesis room with which I began this essay. Macaulay’s eportfolio platform, based in WordPress, provides a range of options for publication and sharing. Students themselves can decide whether to make their final eportfolios public, public only to the Macaulay community, password-protected (so that only individuals to whom they give explicit access can see it), or private. And they can make these decisions in different ways at different times, changing the settings themselves, as they develop the eportfolios. They can also choose to have only certain parts or sections of the eportfolio public, or partially public, at certain times. It’s not an all-or-nothing decision. This gives students the freedom to take risks and explore difficult material, but also to have sharing and taking part in a wider intellectual community as a sanctioned goal.

WordPress is (if the student sets the options to allow this) a platform that is extremely well optimized for search engine discovery. So students’ work, rather than sitting isolated and abandoned, is discoverable widely and by the entire range of learners who might be interested in their topics (to the extent that students share their work). And those external learners, that wider community, have (again, with the student’s control and moderation) the potential to add comments and further the discussion. This openness to participation from an audience is a key feature of the eportfolio. Some students, in fact, in a move that we encourage when appropriate, even actively promote and invite participation from their audiences, through FAQ’s, posting and linking to their eportfolios on social media, or even opening a “share your story” page right on the springboard eportfolio site. (https://macaulay.cuny.edu/eportfolios/storytelling/share/). In some ways this openness to external participation calls into question the traditional definition of an eportfolio. If an eportfolio includes the work of others, rather than just the student herself, is that still an eportfolio? Is it still the work of that student? These are open questions, not just about eportfolios as a genre, but about the overall nature of scholarly inquiry. They are questions that we want students to see as live issues, as philosophical positions on which they can have a stance and to which they can contribute. In making decisions about what kind of sharing what kind of participation they want to offer to readers, even into the future, students are pushed to actively consider and debate, rather than just passively receive, conclusions about research and scholarship that will continue to influence their learning far beyond college.

Not so directly connected to the eportfolio element of this course’s curriculum, but nonetheless critical to our efforts to have students open their projects to a wider audience, has been our commitment to having students present their work in this class publicly at national conferences (such as the National Conference on Undergraduate Research and others). Traveling together as a class, having the experience of acting as members of an academic community and sharing their research with other scholars across disciplines provides the students with a perspective on their work and its place in the intellectual landscape they are entering.

Conclusions and Looking Forward

As the springboard class and its curriculum has developed over the past few years, moving beyond the pilot initiative, we have noticed some surprises. Perhaps connected to the way we originally proposed and presented the course, we have encountered larger numbers of students who have interdisciplinary or otherwise unusual ideas for topics. A major challenge for the course and the students has been pushing the students to narrow and focus these topics. The freedom that the eportfolio curriculum offers, the inclusiveness of digressions and of a range of only minimally connected material, has sometimes been more of an obstacle than a benefit. Yet at the same time, the eportfolio’s emphasis on process and reflection has allowed the course instructors to point clearly and concretely to when these obstacles were arising, and for the students to take the advice (after narrating and processing it in the eportfolio’s research journal) to narrow and specify when necessary (while preserving the digressions and “unrelated” pathways as directions to be pursued in the future).

Another challenge for the course instructors has been that students sometimes undertake projects that have subjects well outside the instructor’s own area of expertise. The math major in a springboard class taught by a historian, or the comparative literature major in the course taught by an ecologist, have challenges that are not there for a more typical thesis project supervised by a professor in that particular field. We work with this challenge by asking for some consulting from colleagues when necessary, but also because one emphasis of the course and the project is in communicating to a wide range of audiences. A student writing a math thesis may have a thesis (that will be included in the eportfolio) that will not be readily understood by a non-mathematician. But the research process, the journaling and the reflection, as well as the student’s own summaries and proposals about the project are readable and understandable (and directed towards) by a wider range of audiences, who can then decide whether or not to read the thesis itself and will certainly have the context required to understand that thesis more fully, even if they are themselves mathematicians.

We also have found (what should not have been surprising) that this curriculum is not a panacea. The eportfolio-centered curriculum, the collaborative support and scaffolding of assignments, the shared commitment to presentation and personal engagement and integration—all of these are helpful for students with a wide range of abilities and levels of commitment to the project. The factors that make this class different tend to have a positive effect on even the weakest students, even those most distracted by life events and stressors. But the class and the project do still require intellectual ability, motivation and commitment. Even in a self-selected group of students, even in a course pilot that is optional and open, we still do not always see that.

Looking to the future, we hope to make this model more prominent, to convert a majority of our current thesis or capstone projects to springboard classes. Already in the few years since our first pilot, we have transferred the instruction of the course to several different professors, all of whom have added their own elements and refined the approach. Each year, the number of students volunteering for this option has grown. There are requirements to successfully implement this type of curriculum. The instructor has to have an interdisciplinary bent (in the 2017-2018 academic year we are experimenting with a team-teaching approach with two instructors and two linked sections of the course) and be willing to work closely with a group of students with varying interests over a full year. The class size has to be small (the amount of close participation in student work through many stages is otherwise too onerous). And the instructor has to be extremely adept in the eportfolio platform as well as the other digital and multimedia tools that the students will want to explore and utilize. At Macaulay, we assign an Instructional Technology Fellow (a doctoral student with both teaching experience and digital technology expertise) to assist in the course, helping students (and the professor, no matter how adept) to use the most current tools for research, communication and presentation, and to incorporate these into the eportfolio.

The eportfolio-centered curriculum of the Macaulay Springboards is developing, for our students, as a productive and powerful alternative to the dusty seclusion of the filing cabinets of the thesis rooms. Students in this program are able to complete projects, to develop eportfolios, that situate their learning in their larger life narratives, that integrate their studies across disciplines and fields, and that give them a place in the wider scholarly and intellectual communities across academia and the digitally-connected world.

Women in STEM

Last week I was at the 2016 Summit of the National Center for Women and Information Technology. It was an interesting conference in several ways (the large, mostly empty, slightly creepy desert hotel constantly evoked the warm smell of colitas), but mostly because of the very powerful keynote by Melissa Harris Perry.

She began by giving us a brief introduction to intersectionality and laying out the issue (a familiar one to this audience) of women’s underrepresentation in STEM, with some compelling (frightening) specifics.

For example, earlier this year, Chanda Prescod-Weinstein was awarded a PhD in theoretical physics at MIT. Nothing really surprising or unusual about that (although good news for Dr. Prescod-Weinstein), until you realize that Dr. Prescod-Weinstein is not just an African-American woman, she is one of only 83 African-American women to receive a PhD in physics or a physics-related field. 83. Not 83 in the past year, or 83 at MIT, or 83 with hyphenated last names. 83 African-American women with PhD’s in physics EVER. In all of American history.

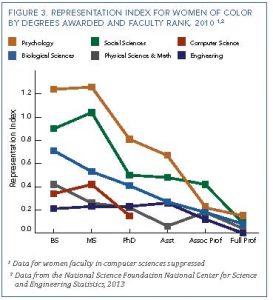

Then Dr. Perry showed us this graph (which I’d seen before, but which shocks every time) from the AAC&U study in 2010. (source)

Those lines show the numbers of degrees and faculty ranks for women of color in various fields. In physics, math, engineering and computer science, the numbers are low from the start. But look how all the numbers dive off a cliff when you get to the rank of full professor.

So the problem is real (and she had plenty more examples, some personal). And the audience knew it, and were more outraged still to hear all the examples and specifics. And Dr. Perry was very good about explaining how very many of the attempts to solve this problem (computer engineer Barbies, coding boot camps, job “opportunities” that don’t address the culture of organizations, internships or training programs that never lead to actual decision-making roles), even when they’re well-intentioned, are doomed to go nowhere, because they don’t address the roots and real causes of the problem. Which, of course, is deep, cultural, and complex.

But, to her great credit, Dr. Perry went even further than explaining the problem and critiquing unsuccessful solutions. (I was at first worried that this was going to end up as one of those “it’s a bigger problem and therefore we have to just throw our hands up in the air” talks) She provided a list of real practical steps, with deep reach and broad foundations, that could actually, systemically, successfully, pave the way to creating and improving real opportunities for girls and women of all kinds to participate in real ways in the STEM careers and academic pursuits in which they are underrepresented.

Here are those steps, as I captured them. Working from my notes, hastily scribbled, I am certainly missing and mis-paraphrasing some of what she said. But I thought this was real enough and strong enough to document.

- Fight voter suppression. This one clearly surprised the audience, as it seemed somewhat unrelated. But Dr. Perry’s link of underrepresentation to questions of policy and power and funding (controlled by the people who are most affected) made perfect sense.

- Reproductive justice and real sex education. Women can’t easily make the whole ranges of choices about their careers and educations if they can’t make choices about their bodies and families and partners.

- Comprehensive immigration reform. So that women can pursue opportunities globally.

- Cite a woman of color. Every time. In every publication, in every talk, always cite at least one woman of color. If you haven’t cited any, don’t assume there are none to cite. There are, and the fact that you don’t know of them is part of the problem, not a reason to continue the problem.

- Follow Black girl leadership. Don’t tell the girls what’s the “right” kind of STEM or of making, let them tell you. Reading, or rocking, or singing or painting, can be just as much a way to learn STEM as coding. Schools (and especially STEM programs in schools) need to stop acting like making art or music in school is some kind of weird distraction or waste of time. (STEAM not just STEM).

- Honor the different intersections of all types of women and girls. Talking about “women and minorities” completely ignores the people who are simultaneously both. Girls and women come in all types of shapes and sizes and races and abilities. Not all women are cis women. Not every girl wants to be an astronaut or an athlete. Lipsticks and head-scarves and boots and suits and leather jackets and fuzzy sweaters all need to be welcomed.

- Community engaged research. Projects and studies that meet the needs and answer the questions of real communities will often work better to engage real people than “Hello World” or fighting robots.

- (Here she quoted Antoine de St. Exupery) “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people together to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” It’s not about specific tasks. It’s not about learning to code or learning calculus. It’s about the endless immensity of the sea. Get people inspired, not about tools but about goals. Not about tasks, but about dreams. (as it turns out, St. Exupery might not have said exactly this. But the point still needs to be made, and I still love it).

- Right to fail. Not just that people have a right to fail, which of course we do, but that it’s right to fail. It’s the exact right thing to do. If you’re not failing, you’re not learning.

(As I said, I’m probably misquoting Dr. Perry, and almost certainly missed some of what she said. 9 points is a start, but only a start. There’s more. But I really love the way she looks at concrete practicalities as well as global principles)

As we at CUNY and all of education and higher education, and as I personally, work to include more opportunities for more people who have been left out of STEM (STEAM), I want to remember these as principles to work with. And I would love to hear more discussion of all of them, at all levels. Let’s talk about specific programs and initiatives, sure. But also about bigger challenges and wider changes that address the real issues.

The Technology of Smarthistory

(A long and technical post follows. If you don’t care to read it, if you’re of the TL;DR school, then go, right now, to Smarthistory.org and take a look at what kind of a beautiful OER can be made with WordPress.)

As anyone who knows me knows, I’m a big supporter (and helper, I guess) of Smarthistory (one of the most important Open Educational Resources on the web). I’ve been involved since the beginning. I’ve posted about it before, more than once. But Smarthistory has just reached another important milestone. For years it was an independent stand-alone website, with several different designs. The original iteration was in WordPress. I built that one, and it looked…well, see for yourself.

That site was the beginning of Smarthistory and it did a lot of the good things that Smarthistory still does. And I was proud to have built it with open source tools and for free. It even won an award, because it did work.

Then there was a small grant and a new design and new site in another open source CMS, ModX. I didn’t build that one, and the design was much better as was the functionality.

That one actually won another award, a Webby, and got a lot more attention. It was a great and beautiful site. Then Smarthistory became part of Khan Academy, and eventually keeping up the separate website wasn’t viable anymore. So the Smarthistory site went to the Internet Wayback machine.

Well, now, once again, Smarthistory is an independent site! Beth and Steven have a blog post announcing and explaining the new setup. And what their goals were.

The new site is even more gorgeous than before–I think–and even more functional. Some of the goals (as Beth and Steven explain) were to make the art the beautiful center, and to use the menus as teaching tools. That point–that information architecture can be a kind of pedagogy, is one that I hope to take up at some length in a later piece. Here I just want to detail, for those who might be interested, just how I made the site happen with WordPress and gave it the kind of elegance and functionality it needed to have.

So let’s dig into some of the technical details.

Smarthistory is running on WordPress, hosted by the wonderful folks at Reclaim Hosting.

Smarthistory is using a child theme based on the Customizr theme. This is a very bare-bones theme, and very clean (letting the images take the stage). It is also somewhat difficult to work with, since it doesn’t use exactly the standard WordPress setup of template files, and all the functions are controlled by hooks…which are sometimes not so well documented.

That child theme uses quite a bit of custom css (and, unfortunately, a lot of the !important declaration. I know that’s not usually best practice, but in this case it was often necessary). In some cases I had to use CSS to duplicate what customizr does for some of its non-template templates. One example of that is the Popular Now page, which, like the Browse by Image pages, came out particularly nicely.

There’s also a rather extensive custom functions.php file. (I’m happy to share both of those, in detail or in full, if anyone wants).

And then there are the plugins…we’re using a lot of standard ones (akismet, for example), but there are some really special ones we discovered and used. Here are the most important–all highly recommended for anyone working on any kind of similar project. Most are free.

Ajax Search Lite provides the really powerful and image-friendly (with thumbnails!) search bar.

Co-Authors Plus allows us to have authors listed for articles (and even more than one author, hence “co-authors”) who do not have to have an account on our WordPress system. Even better, it gives us (with some special help from the great Daniel Bachhuber, formerly of CUNY, who originally wrote the plugin) a very beautiful and functional alphabetical list of all the site’s contributors. And each of them has a particularly nice author page.

Maps Marker Pro let us make custom maps which are so important to telling historical stories.

NextEnd Accordion menu let us have very specific and contextual left-side nav menus, different on different pages (the top-nav is a different plugin–see below).

Ubermenu gave us that top nav. This is an absolutely amazing responsive menu, and when a site has such a large and complicated structure, this is critical.

Of course the site is Creative Commons licensed…and I consider that goes for the technical details, too. So anyone who has questions about how we made things or made them work…I will always share and answer!

To make a site with (literally) hundreds of pages and (literally) hundreds of different menu items, and to make that into a resource that teachers and learners anywhere can use anytime for free…I am so happy and proud to have been involved with that! And I should also mention the great assistance of Gwen Shaw and Nara Hohensee, both CUNY colleagues, who put in long hours and excellent work in getting the site ready for launch.

A long and balanced MOOC report

I was interviewed for this report, although my role was small, and now it’s out, and I think worth a read. It’s long, but that means it’s comprehensive. I was impressed by the real openness and curiosity of the researchers and the way they didn’t start with preconceived notions.

So give it a read: MOOCs: Expectations and Reality

STEAM

Thanks to Michael Branson Smith for the great tip to listen to Adam Savage’s talk “Why We Make” at the 2012 San Francisco Maker Fair.

Savage explains with some brilliance how art is always part of STEM (art is where it all begins), and how learning works best when it comes through “making what you can’t not make.”

This is just an excerpt from the end of the talk, the part most relevant to teaching and learning. The entire talk is well worth a listen, but for those with limited time, this clip is the heart of it.

Smarthistory and the Google Art Project

Big news today in the world of art–and the world of teaching and learning with and about art–and the world of “jailbreaking” the museum (or access to all kinds of cultural knowledge).

Actually it’s two items of big news.

The first is Google’s announcement of version 2 of their already tremendous Google Art Project. They’ve now got 151 museums, from 40 countries (up from only 17 when they first launched). That’s 32,000 works of art. But these are not just little clipart low-quality watermarked jpgs. They’re gorgeous, high-resolution, full color, zoomable, suitable-for-study images. For some of them there is even “museum view” which lets you simulate walking around the museum and seeing the art in the context where it currently sits.

And then there’s the other fact, which of course has a strong personal resonance for me (on many levels!). For quite a few of these works of art (over 100), there are videos made by the wonderful folks at Smarthistory. Of course these add to the enjoyment, the understanding, the learning, the questioning of the art. A great example, a favorite of mine, is Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s Tower of Babel. It’s fantastic, with so much to see, but it’s in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Except now, it’s not only there, it’s also got a version on the Google Art Project. Take a look. Zoom in. Pan around. Really see what’s happening there. And then click on the “Details” link at the top of the screen, and you won’t only see the “normal” kind of details you might expect (description, map, style, material), but you’ll also see a video.

And that video, like over 100 others on the new Google Art Project, comes from the one and only Smarthistory team. Conversational, informal, engaging, informative and provocative…just what we want and expect and need!

As the Smarthistory team says in their announcement:

We jumped at this opportunity because the Art Project has such enormous educational potential. It is critical to gather works of art from different institutions to tell the nuanced stories of art history. The Art Project brings together works of art from 151 museums in 40 countries within a cohesive visual environment. The high resolution images, powerful zoom function, “Museum View” (an interior version of “Street View”) and the ability to collect and annotate images, are all features that are ideal for teaching and learning.

Viva the Museum without Walls!

“Rebuilding the LMS”

Campus Technology has a feature this month on “Rebuilding the LMS for the 21st Century.” The reporter interviewed me at some length a few weeks ago, and did a pretty good job of capturing what I said. All in all, a pretty good article. Of course, I would probably say it’s better to throw the LMS away and build something flexible and open. But I guess that’s really what I said…

Not at all a bad interview, and if some of it is a bit aspirational, it is still, in essence, what we’ve done and are trying to do.

The first MIT.x course

MIT has opened enrollment for the first of the new MIT.x courses, “Circuits and Electronics.” The course is free, and in this first pilot instance, even the certificate gained for completing the course successfully will be free (MIT expects to start charging for those some time soon).

6.002x (Circuits and Electronics) is designed to serve as a first course in an undergraduate electrical engineering (EE), or electrical engineering and computer science (EECS) curriculum. At MIT, 6.002 is in the core of department subjects required for all undergraduates in EECS.

The course introduces engineering in the context of the lumped circuit abstraction. Topics covered include: resistive elements and networks; independent and dependent sources; switches and MOS transistors; digital abstraction; amplifiers; energy storage elements; dynamics of first- and second-order networks; design in the time and frequency domains; and analog and digital circuits and applications. Design and lab exercises are also significant components of the course. You should expect to spend approximately 10 hours per week on the course.

“Great!” I thought. “I can do that! I will try it! Sounds like a fascinating subject, and way back in high school I did think that I might become an engineer. And it will give me a chance to try out and blog about the new MIT.x platform.”

But…no.

In order to succeed in this course, you must have taken an AP level physics course in electricity and magnetism. You must know basic calculus and linear algebra and have some background in differential equations. Since more advanced mathematics will not show up until the second half of the course, the first half of the course will include an optional remedial differential equations component for those who need it.

That rules me out, I’m afraid! For about six different reasons. And, I think, it should rule out some of the complaints/skepticism about these courses. We can (we should, we will) make learning more open and more accessible. But in some very important ways, there really aren’t any shortcuts. Engineering is engineering, and it can be open to everyone…but it’s still engineering, and without the physics and the math, it just isn’t going to be understandable.

Still, I hope someone reading this who does have those basic qualifications will give it a try and blog about the experience! You can enroll here 6002x.mitx.mit.edu.

Of iBooks and textbooks. And Authoring. By Students.

So there’s been a lot of excited posts–positive and negative–in a lot of different places about Apple’s announcement last week that they were ready to “revolutionize” the world of textbooks. Some of the best of those that I’ve seen are from Audrey Watters at Hack Education and Kathleen Fitzpatrick at ProfHacker (both of these are mainly critical). (And just as I’m writing this post, I see that Michael Feldstein at e-literate has weighed in with his usual sharp brilliance!) And there have been some other good ones, too. I think a lot of the criticism has been warranted. And a lot of the excitement has been justified.

But I think that even the best of these have missed some important points, and misunderstood some others, so I wanted to give my own take.

A couple of opening premises: I have felt for quite a while now that the “textbook” as an entity (a genre, a medium, a format, whatever it is) is long past its expiration date. The extremely expensive physical book, which all students are required to purchase, which digests the critical information on a given academic subject, is something that was ever only of very limited value, and whatever value that was is pretty much long gone. (And “digest” is really the right word there–what these books do is take subjects and chew them up and pre-process them, so that they can be metabolized without effort…and without flavor or pleasure, either. A textbook is to learning what Ensure® is to fine dining.) The monopoly aspect, the new editions every year without any real content, but mostly the deadening effect on the learning, made me stop using textbooks in all my classes years ago. I use books, not textbooks (and sometimes not even books, but that’s a separate topic). Of course this is easier to do when teaching English…but I don’t think it’s impossible in any subject.

So I’m no fan of textbooks, but I have known and do see that they’re not exactly an escapable dinosaur right now. Teachers with little time to innovate resources, or teachers mandated by a centrally-determined curriculum, or teachers who have found textbooks they really do like and find engaging and useful are still going to need to have those textbooks be as good as they can be–and as affordable and usable as they can be.

It seemed right from the start that Apple had knocked out a couple of the big problems with textbooks. A cap of $15 is a big savings. The ability to include video, 3-d objects, interactive charts and graphs, in-line review quizzes and hyperlinks adds a lot of new ways to engage with content. And of course the reduced schlep-factor is an advantage.

And an easy and convenient (like iTunes) distribution method (cutting out the gouging of many campus bookstores) could help, too.

So I tried this for myself. I updated my iBooks on my iPad. I installed iBooks Author and started messing around with creating a textbook. I downloaded the free (and beautiful) sample of E.O. Wilson’s Life on Earth. And I spent the $15 on Miller and Levine’s Pearson textbook Biology. They definitely are beautiful. And they definitely have the advantages that an iPad can give. The video is terrific and plays smoothly and is integrated well. The interactive demonstrations and graphs helped me to understand the concepts. The photography in brilliant color, swiping to change photos and pinching to zoom, and the rotating and manipulable 3-d objects are terrific. I took some quizzes and checked my answers and found out why I was missing what I was missing. That was all great. But what was still disappointing to me was that these are still textbooks. They still have that same bulleted, condensed, digested approach to the content. I got to read about what Darwin thought, but I didn’t get to read Darwin. I got to see examples of what the book said I should know, but not look at examples and determine for myself what they told me.

I have been having a problem with almost all the ebook initiatives for schools that I have been reading and hearing about. I can’t really support them, because they almost all see text as being something that can be just seamlessly translated into an electronic version and then left there. That’s fine as far as it goes, but it doesn’t go far enough. A textbook on a screen that is just text, without all the advantages that a screen can give (media, links, and so on), just seemed like a big waste to me. And now I’ve found that even a beautiful multimedia textbook on a screen, taking advantage of what a screen can do, if it’s still a textbook…it’s better, but it’s still not good enough.

Now, there are also the disadvantages that are described in the posts I linked above. There isn’t a means for interaction among students. There isn’t as much of a savings for school districts where they have always purchased one set of books per class, to be re-used each year. iPads are expensive and breakable. And so forth. Those are real. But they aren’t to me the real disadvantages.

However. And this is a big however and the main point I wanted to make. There’s something else going on with this announcement, with this offering. And that something seems to be missed in almost every post or reference I’ve seen. In addition to iBooks and the publisher-created textbooks for sale, Apple is also offering, as a free download, iBooks Author. And that’s where things get really interesting. Nobody has really missed that this product lets teachers create their own textbooks. And then offer them to their students (or anyone else). Like any Apple product, iBooks Author has some incredibly beautiful ease of use features. Like any Apple product, if you want to go outside the bounds of what Apple has predicted you will want to do, it’s frustrating. And like any first-generation product of any kind, there are some bugs and issues (particularly with previewing and exporting) which will be resolved in future updates, to be sure.

It’s a giant time vampire, too–in a good way, though. It’s very easy to get involved in adding this, arranging that, moving things, aligning things, thinking about where a picture would help or video or a hyperlink would be good or a glossary entry is necessary. But some of this is actually very good thinking work, making decisions consciously about how to arrange and present content.

And that, right there, is what might be the real value in this product. Not in having teachers create textbooks which they will then push out to students who are required to use them. Like iMovie, like GarageBand (and yes, with their frustrations and problems), iBooks has the potential to put the creation into the hands of students. That’s where we can have some exciting results, some really gorgeous and useful products. Even better than that, it’s where we can have some vital and powerful processes. When students create content, when they actively and critically think about what should be in their “textbook,” when each student (or small group of students) can create their own “textbook” and share it easily and actually get an audience who will be critical and responsive…that has the potential to be actually revolutionary. They get the experience of doing the chewing, the swallowing, and the savoring (and even the creating the recipe and the cooking, if I’m not pushing the metaphor too far).

I will certainly make a textbook (more than one). But I will also use the tool to think through how students can create something (some things) that aren’t really textbooks at all (although for convenience we might call them that. Or maybe call them “untextbooks”). A tool that lets students interact with course content in a way that is creative, expressive, and distributable, is a tool that I can use, that I’m excited about using, and that can really benefit students.

I’ve seen (everywhere!) the strong criticism that these textbooks, whoever creates them, are really only usable on iPads. That’s true (although I’m not sure how permanently true that is. I remember when music bought from iTunes could only be played on an iPod, and that’s not true anymore). Even if it’s only temporarily true, it’s a valid criticism.

I’ve also seen (also everywhere, and even more angrily) the stronger criticism that Apple’s EULA on iBooks Author is too too restrictive. That you can only sell the content you create through the iBooks store. Only. That’s true, too…but I care a whole lot less about that one. Because Apple has also included, very explicitly, the condition that if you make your content free of charge, you can distribute it any way you want. No limitations. We need a bigger universe of free content, and this model could (will, I think) help to promote that. If you want to sell, sell through Apple. But better yet…don’t sell. Give it away. Let Pearson and McGraw Hill continue to sell their books for $15 or whatever they want. We (we including our students) can make better content–things that are not just textbooks, but new kinds of representations in multimedia, for free, and we can give them away for free. And we can use Apple’s distribution channel…or not.

We do have to find ways to make these new things (untextbooks) useful on more than just the one kind of device. I doubt that will be far off. An online iBooks format emulator? A translator to HTML 5? There will be a way, I’m sure.

Look for my untextbook Quacks, Yokels and Everyday Folk, coming soon!

Early thoughts on Pearson’s OpenClass

This was a major topic of conversation at Educause last week, and I had the chance to chat briefly with Adrian Sannier of Pearson on the exhibit floor–and also to try it out myself.

A few quick facts/impressions. A lot of the early buzz was about “Google’s new free and open source LMS” or similar. Almost none of that is accurate. It’s not a Google product, it’s a Pearson product. It’s available (for now) through the Google Apps marketplace, and integrates (or will–this week, they’re promising) with an existing Google Apps for Education database if you have one. But everyone I talked to from Google was very quick to point out that they didn’t develop this, aren’t offering it, don’t really have much of anything to do with it. They marched me straight over to the Pearson folks if I even tried to ask a question.

It’s also not at all Open Source. Pearson uses the term “open” very very loosely–so far I haven’t seen anything at all open about it. Adrian Sannier says that that is coming–some way for teachers to identify parts of their courses that could be shared with a wider network, multiple campuses or maybe all users of the system or maybe the whole world. But that’s not available yet. And the source code is definitely not open or available. There aren’t even API’s yet (although again, Adrian promises that there will be).

What is, however, is free of charge. That’s the main “selling” point, and when asked if that’s the distinguishing feature he would most want to claim, Adrian was very clear (both to me and to my friend Michael Feldstein. Michael has a very good blog post about OpenClass here ). This is not going to cost anyone money–free as in free beer, not as in free speech–and that’s what they’re proud of and what they’re promoting.

For now (and this should change sometime early in 2012), OpenClass is only available to Google Apps for Education campuses. Since we at Macaulay do use Google Apps for education, I (like hundreds of others) went immediately after the announcement and installed OpenClass to check it out right away.

I could talk at some length about what I discovered in testing–and we’ll be doing a lot more testing and trying (maybe for some spring classes, perhaps) as time goes by. It’s still very much in beta, with some features that aren’t quite working yet–some of them essential–and some little bugs that they’re still working on. The Pearson people seem to be extremely committed to fixing those bugs–they are responsive on twitter and by email, and in fact, when I pointed out a bug to their folks at Educause at about 3 in the afternoon, they called me back with more questions within 45 minutes, and then had the problem fixed by dinnertime that same day. That’s impressive, and not something that most LMS vendors would ever dream of doing for an end-user. That kind of response is reserved for high-level “escalated” tickets. Will that last? Who knows. But it did leave a good taste in my mouth.

As for the product itself, even given that it’s in beta, I have to say and somewhat hate to say that I’m not all that impressed. It’s an LMS. A fairly ordinary LMS. It’s not got revolutionary features, and the so-called social networking integration (mostly just an activity wall pulling together everything that is happening throughout the LMS for a given user as a main front page) is pretty much a big meh. The discussion board is not particularly attractive or navigable, and the general features (gradebook, announcements, submission/dropbox, assignments, documents) are just standard. Functional, but nothing interesting. The design is fine, but not very elegant and hardly customizable at all.

This is a standard LMS for a class (not a fully online class, Pearson is trying to make that distinction very clear) where a teacher and students want to do the basic LMS stuff–post a few things, assign and submit a few things, check grades, have a little bit of discussion–mainly just for asking and answering questions, not what I call a “real” online discussion (wide-ranging, digressive, engaging, critical, multi-media). Multi-media capabilities are limited. Sharing with the world outside the classroom, or escaping the silos of course and semester that the LMS is so married to, are both just about non-existent.

But all of that could come. At least for now, the promise or potential for most of that seems pretty strong. And one thing that Adrian also pointed out–with a free LMS, upgrades and new features can come much more quickly and easily. Most of the time, they will come fairly transparently. Nothing at all like an “enterprise” LMS upgrade. So that all remains to be seen.

I’m really interested to see how this will open beyond Google Apps for Education. When (and again, it could be just a few months) this opens up more widely, will that be to all Google customers? So that if I’m not affiliated with any institution, but I want to (for free) set up a class where I could teach and/or learn about birding or reef aquaria or the history of haberdashery, can I do that? And can I do it in a way that will make sense for learners–not just for a traditional class/semester-based type of education? Open questions!

I will also say that OpenClass is still a long, long, way from being even a bit close to the kinds of features and functionality, and from the kind of “disruptive” innovation that we are already seeing and demonstrating and doing at Macaulay (and elsewhere, of course) with WordPress. It’s like some of us are already working with refining a very low-cost and efficient warp drive technology, while Pearson has just introduced a fairly nice three-speed bicycle which they will give away for free.

But…when the overwhelming majority of classes in this country are riding around right now on a ten-speed bicycle, for which they are paying $100k a year (or whatever), a nice shiny three-speed for free is going to sound like a pretty good deal. If possible, though, I’m always going to want to do the deeper exploration that a cruising speed of warp 6 or 7 can allow.