Macaulay Social Network Moving Along

With the recent announcement (finally!) of the release of BuddyPress 1.o, I took the opportunity to upgrade the Macaulay Social Network site, and give it a light touch of redesign. (Also partly inspired by the great work with BuddyPress right here at the Academic Commons, I must admit!). We had a very successful period of piloting with the beta version(s), and even though it wasn’t supposed to be used in production environments, it seemed to serve very well. There were a few small but annoying bugs, and it’s really looking like the upgrade has now fixed all of those. I’ve got the summer now for more testing and tweaking, and I’m expecting to see very heavy usage from students this fall. There are features (the directory, the searchable profiles, the messaging, the groups) which our students have really been requesting, and it will be great to see how they help us continue to connect the Macaulay Community!

With the recent announcement (finally!) of the release of BuddyPress 1.o, I took the opportunity to upgrade the Macaulay Social Network site, and give it a light touch of redesign. (Also partly inspired by the great work with BuddyPress right here at the Academic Commons, I must admit!). We had a very successful period of piloting with the beta version(s), and even though it wasn’t supposed to be used in production environments, it seemed to serve very well. There were a few small but annoying bugs, and it’s really looking like the upgrade has now fixed all of those. I’ve got the summer now for more testing and tweaking, and I’m expecting to see very heavy usage from students this fall. There are features (the directory, the searchable profiles, the messaging, the groups) which our students have really been requesting, and it will be great to see how they help us continue to connect the Macaulay Community!

A Webby Award for Open Education

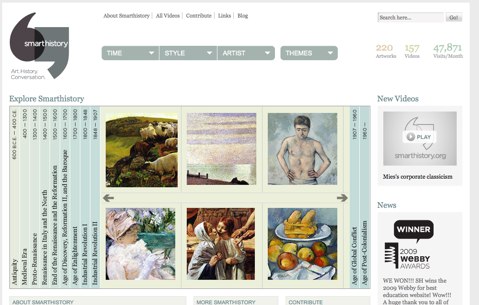

The annual Webby Awards (what the NY Times calls “the internet’s highest honor”) were announced today, and in the education category, the very-deserving winner was the excellent Smarthistory.org site (full disclosure–the site is the work of my wife and her colleague, and I’ve had some marginal technical involvement in it myself from the beginning). Smarthistory is an educational site actually designed and built by educators–two art historians who wanted alternatives for teaching and learning. Dissatisfied with what textbooks, or even ArtStor, could offer, and not interested in closed models or walled gardens, they started from scratch with open source tools (beginning with WordPress, and now using ModX). The site is dedicated to open sharing of educational resources, and makes full use of the tools and abilities of Web 2.0. It’s about art and history…and even more about conversation and interaction around those. But it’s hard to describe–better just to experience it. To see a site like this win this prestigious and competitive award, beating established museums and huge well-funded foundations, is more evidence of how when things get done right, they work!

The annual Webby Awards (what the NY Times calls “the internet’s highest honor”) were announced today, and in the education category, the very-deserving winner was the excellent Smarthistory.org site (full disclosure–the site is the work of my wife and her colleague, and I’ve had some marginal technical involvement in it myself from the beginning). Smarthistory is an educational site actually designed and built by educators–two art historians who wanted alternatives for teaching and learning. Dissatisfied with what textbooks, or even ArtStor, could offer, and not interested in closed models or walled gardens, they started from scratch with open source tools (beginning with WordPress, and now using ModX). The site is dedicated to open sharing of educational resources, and makes full use of the tools and abilities of Web 2.0. It’s about art and history…and even more about conversation and interaction around those. But it’s hard to describe–better just to experience it. To see a site like this win this prestigious and competitive award, beating established museums and huge well-funded foundations, is more evidence of how when things get done right, they work!

Are we totally missing it?

Sometimes a comic really hits the real points…

The Producers

We gave all our incoming freshmen Flip Cams this past fall. These are very small digital camcorders. They are small enough to be carried all the time, ridiculously easy to use (no cables, and basic software is already installed right on the camera itself, and using AA batteries), and the video quality is quite acceptable, especially for YouTube.

My thought was that these would be useful for the walking tours, interviews, and other elements of the neighborhood websites our students produce for our Seminar Two (“The Peopling of New York”). But I didn’t foresee all the many uses they would actually serve. Students used them for videos in Seminar One (“The Arts in New York”), and some (sophomores) borrowed and used them for PSA’s they created as projects for Seminar Three (“Science and Technology in New York”). Others are even asking for them for Seminar Four (“Planning the Future of New York City”). Our students and faculty in the alternative spring break service learning program (in New Orleans–“The City that Care Forgot”) are using them to document that work, and a student working on an independent research project on Obama’s first 100 days has one, too.

And in this year’s Snapshot NYC event, students had the chance to create an entirely new type of project, “re-curating” the photo exhibit (of their own photos) that we had posted in the building.

Much of this is available on our YouTube Channel, so it’s searchable in YouTube, it can be seen by the multitudes of the public, commented on, made into favorites and followed.

And then at this year’s Yield Event for our newly-admitted students, I met a student who asked me if we would be giving the flip cams to freshmen again in the fall. When I told him we planned to, he said he was glad and said “you know, all the kids in my high school know about Macaulay because of those flip cams.” It seems that those YouTube videos are being seen by all kinds of audiences, including our own prospective students. As others have noted, YouTube these days is not just for funny cat videos–although the appeal of those is undeniable!–it’s also a first-choice research tool, especially for young people.

But there’s more than that. I had been thinking about “student stories” for our re-designed website, as well as videos of faculty and tech fellows and even staff. But I had been thinking “Oy, what a chore to have to film all these and edit them and post them.”

I was thinking in the old way. The students not only have flip cams, they use flip cams. And they post and share what they make with those flip cams. There don’t have to be (at least not all the time) centralized or official producers anymore, because they/we are all producers.

This is what students are showing us–with the flip cams, with the eportfolios, with so much that we do. We give them support and tools, and they use those tools and that support to produce.

What they produce might be rougher or less polished, or it might not be. But it’s theirs and it’s what they’re used to, and there’s a multiplier value, or several of them. They can produce things that we never expected, that we wouldn’t have thought of, that might be much better than what we thought of. And they get to learn from the producing, so the actual process of documenting their learning is another type of learning activity. And they get to learn from the sharing, too, when they interact and become engaged with a larger wider audience.

School 2.0 Will Not Be in School

We’ve been talking throughout the semester in the Core II class in the ITP program about the idea of “School 2.0” (which I’ve also explored as “the University of the Future“). It wasn’t really an intended theme of the course, but we do seem to keep coming back to it.

And at a meeting recently I heard someone say “you could take a professor from the 19th Century, and drop him into one of our classrooms, and aside from some of the technology, he would be completely familiar with everything that was going on there. It would all look just the same as what he was used to.” This was said somewhat approvingly, as a measure of how we’re doing things right. But I don’t think it’s right. It’s probably not even true, but if it is, it’s not a good thing at all.

Over the weeks I’ve been thinking more and more that we’re missing opportunities if we’re not keeping up with what happens in terms of learning outside of that same-old, same-old sphere. It’s probably always been true that just as much (or more) learning goes on outside of classrooms as inside, but we’re entering an era where there can actually be recognition and formal acknowledgment of that, and if we in higher ed want to cling to our exclusive role as credentialers of learning, we’re going to lose the race and be rendered irrelevant.

Knowing how to ask becomes a more important skill, a more useful credential, than a score on an exam or a grade in a course, in a world of open access to educational resources. Something like whuffie, or the respect of a group of peers who know your work in a digital environment, becomes a real transcript or references. An eportfolio (made up of small pieces loosely joined) is more effective and more persuasive than a CV.

And none of these credentials are going to be judged exclusively by what the university thinks of them. Our role has to be to guide and support, to be a resource.

This is why I think that to some extent Mark Taylor misses the point in this morning’s New York Times. He’s totally right that we need a restructure, that the old disciplinary boundaries and holding to tenure when it prevents innovation need to go. He’s completely correct that students need to work on different sorts of projects than dissertations that won’t be published (or even read).

But there is a School 2.0 coming, and it doesn’t take place in school at all. It takes place in blogs and discussion forums, on wikipedia and twitter and digg and instructables. In order to have relevance to students who do most of their learning outside of school, we need to be outside of school ourselves. We need to be teaching and learning where teaching and learning is going on.

That does put us at risk–our authority, our own credentials, are no longer unquestioned or unquestionable, and we lose a certain amount of prestige. But we stand to gain, in learning for ourselves and making our teaching more effective and powerful (and collaborative!), much more than we lose.